Before Egypt: Nubian–Egyptian Migration History

The history of human civilization is often recounted through the lens of well-studied cultures, but to truly grasp the roots of Egypt’s civilization, one must explore the lesser-known yet crucial contributions of pre-Egyptian Nubian civilizations. This region, centered on the Nile Valley south of Egypt, gave rise to sophisticated societies whose influences would shape the course of history in North Africa and beyond. The wealth of the region laid the foundation for powerful kingdoms.

The portrayal of ancient Africans primarily as outsiders interacting with ancient Egypt risks undermining the rich and complex heritage that is deeply rooted within the African continent. This narrative often simplifies the identity and contributions of the African indigenous populations of ancient Egyptians, largely ignoring the fact that they were Africans themselves, with a vibrant culture that predates many of the interactions often highlighted in historical accounts. The portrayal, also divert attention from the reality that the ancient Egyptians were not merely subjects in a broader African tapestry; they were influential stakeholders who contributed significantly to the advancement of culture, science, art, and architecture within Africa. These Africans, and their civilization drew from and contributed to the vast heritage of the continent. Their achievements, such as monumental architecture, sophisticated writing systems, advances in medicine, and mathematics, cannot be divorced from the African context. To suggest that their accomplishments are merely the product of external influences effectively diminishes the role of the indigenous people of ancient Egypt, framing them as mere recipients of external knowledge rather than as innovators in their own right.

Again, the selective acknowledgment presents a skewed understanding of Africa’s history. It cultivates a perception that the cultural and intellectual advancements of Egypt were largely imported, rather than organically developed from a robust African heritage. The magnificence of the pyramids, the depth of religious practices, the complexity of social structures—these elements are fundamentally tied to an indigenous African identity that deserves celebration and recognition.

The Nubian movement to Egypt predates the rise of civilization in the Nile Valley and is a crucial chapter often overlooked in the narrative of ancient history. This neglect can primarily be attributed to several intertwined factors that shaped early Egyptology and influenced how we understand African contributions to civilization.

Firstly, the early days of Egyptology, roughly spanning the 19th and early 20th centuries, were distinctly Eurocentric. Scholars of this period often prioritized European perspectives, leading to the marginalization of African narratives. The lens through which history was examined frequently downplayed or entirely ignored the essential roles played by African cultures, thus creating a skewed understanding of Egypt’s past. Rather than recognizing Nubia’s significant influence on Egypt, early Egyptologists tended to treat Nubia as a peripheral area, which in turn distorted the story of cultural exchanges and migrations between these regions.

Secondly, significant archaeological sites in Nubia faced irrevocable changes due to the construction of the Aswan High Dam in the 1960s. The dam led to extensive flooding that submerged many important Nubian sites, such as the temples of Philae and Abu Simbel, which were part of a significant cultural heritage. Consequently, vital artifacts and evidence that could showcase the Nubian contributions to Egypt were lost or rendered inaccessible. This catastrophic event not only severed ties to historical sites but also limited ongoing archaeological research that could have illuminated the rich interactions between Nubians and Egyptians.

Moreover, the historical removal of artifacts from Nubia further fragmented the narrative. During the colonial era, numerous invaluable items were taken from their original context and displayed in Western museums. By scattering these artifacts across various institutions, a holistic understanding of the Nubian contribution to Egyptian civilization was severely compromised. The dislocation of these artifacts removed them from their cultural and geographical significances, reducing the opportunity for a comprehensive study of how Nubian culture and society intertwined with that of ancient Egypt.

Finally, the broader context of scholarship around African history has often been characterized by biases that echo throughout the academic world. The narrative has frequently been dominated by voices that overlook the importance of indigenous contributions, leading to an emphasis on narratives that do not adequately reflect the intertwined histories of Nubia and Egypt. This has often left the story of Nubia’s movement to Egypt shadowed, preventing a full appreciation of the dynamism and complexity of pre-civilization interactions. Several factors collaborated to obscure the significance of the Nubian movement to Egypt before the rise of civilization. Armed with the knowledge of these historical oversights, contemporary scholars and enthusiasts can strive to unravel and rewrite the narratives of African contributions to civilization, enriching general understanding of the ancient world and appreciating the profound connections that have emerged throughout history.

In recent years, there has been a growing movement among scholars and cultural commentators to reclaim the narrative surrounding ancient Egypt and its people. This resurgence emphasizes that ancient Egyptians were not only Africans by geographical definition but also by cultural lineage. They were part of the broader narrative of African history, characterized by a multitude of civilizations that existed long before external influences became prominent. Such a re-examination not only honors the legacy of the ancient Egyptians but also plays a crucial role in reshaping contemporary understanding of African heritage as a whole. By depicting ancient Egyptians as the rightful heirs of the African legacy, a much-needed rectification of historical misrepresentations that have contributed to the misconceptions of pan-African identity is fostered.

To fully grasp the richness of ancient Egyptian history, it is essential to recognize the vital contributions and influences that arose from sub-Saharan Africa. This understanding requires a reevaluation of historical narratives and calls for a more inclusive approach to scholarship that embraces and highlights the African context of Egypt’s past. By addressing the biases of previous historiography and acknowledging the multifaceted relations between these regions, we can appreciate the true legacy of ancient Egypt—not as a civilization apart, but as an integral part of the broader African tapestry.

The portrayal of Nubia has often been limited to a simplistic dichotomy, where it is seen either as an adversary or as a mere source of resources for Egypt. In truth, Nubia was home to its own rich traditions and innovations. The consequences of these Eurocentric narratives are profound and extend beyond academic discourse. They contribute to a wider misunderstanding of African history and heritage, leading to a perpetuation of stereotypes that ignore the continent’s contributions to global civilization. By framing influential figures like the Nubian pharaohs as outsiders, the historical context of Egypt’s African roots is neglected, fostering a distorted view of historical timelines and achievements.

In examining the significance of Djoser’s statement, the “mountain of the moon” symbolizes the majestic Rwenzori Mountains, which lie on the borders of Uganda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. These mountains are central to the sources of the Nile, a river that has been revered not only as a lifeblood for Egyptian civilization but also as a conduit for the exchange of ideas, trade, and cultural practices. Throughout millennia, the Nile has acted as a natural highway, facilitating movement and interaction between various groups. The narrative of the Nile is punctuated by legends and texts that speak to the significance of this river and its origins. The civilizations that flourished along its banks were not insular; they were part of a larger world that included the interplay of various ethnicities and cultures. Each encounter added depth to the cultural fabric of Egypt, reinforcing Djoser’s words as not just a historical footnote but a testimony to the enduring connections that defined the Nile corridor. In contemporary discussions, the recognition of this interconnectedness remains crucial when exploring the root of the African identity shaped by historical narratives. The understanding that ancient Egypt did not exist in isolation encourages a re-evaluation of how cultural legacy and identity is perceived. It prompts the contributions of neighboring regions to be acknowledged, fostering a greater appreciation for the complexities and diversities that mark the African landscape. Thus, Djoser’s invocation of origins.

The Nubian made exquisite contributions that not only defined their time but also enriched the entirety of the African continent. As modern historians and archaeologists continue to study the remnants of these ancient societies, the true significance of Nubia’s achievements becomes increasingly clear, inviting a deeper appreciation for the intricate tapestry of human civilization.

The A-Group culture, which flourished from approximately 3800 to 3100 BCE, represents one of the earliest known civilizations in the region that would later give rise to ancient Egypt civilization. This period predates the unification of Egypt, providing a critical backdrop for understanding the sociopolitical and cultural developments that preceded this significant historical milestone. During the period spanning from around 4000 to 3100 BCE, a significant transformation occurred in the ancient Nile valley, particularly in the regions that we now identify as Upper Egypt and Nubia. In Nubia, particularly in the A-Group culture (circa 3800–3100 BCE), a vibrant civilization flourished, characterized by advanced agricultural practices, burgeoning trade networks, and distinct artistic expressions. This cultural progress in Nubia coincided intriguingly with the predynastic phase of Egypt, known as the Naqada period, which was marked by the early formation of a proto-state in Upper Egypt.

As the A-Group society in Nubia developed its unique identity, Upper Egypt’s Naqada culture was evolving simultaneously, facilitating the emergence of powerful regional centers such as Naqada, Hierakonpolis, and Abydos. These locations became pivotal in the consolidation of social hierarchy and administrative practices, laying the groundwork for the future unification of Egypt. The Naqada period itself can be divided into three distinct phases—Naqada I, II, and III—each representing increasing complexity in social organization and artistic achievement.

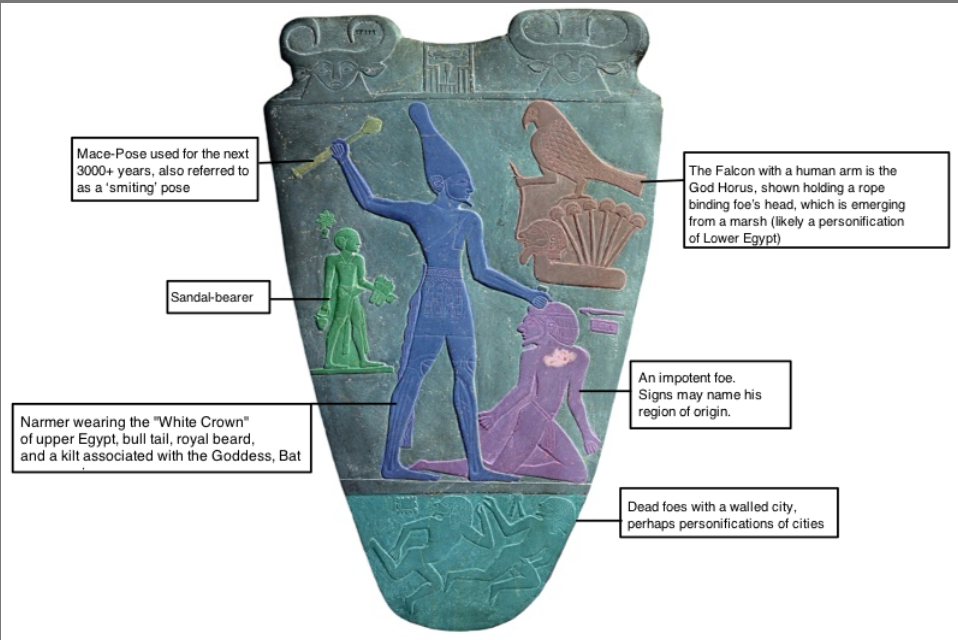

Central to Egypt’s transformation was the rise of political structures that would enable the eventual unification of the kingdom under Narmer around 3100 BCE. Narmer, also known as Menes, is often credited with uniting Upper and Lower Egypt, thereby inaugurating the era of Dynastic Egypt. This event marked a significant turning point not only in Egyptian history but across the ancient Mediterranean world. The unification process was gradual, rooted in the increasing political and economic interactions among the prominent cities and chiefdoms of the Nile Valley.

Here are several authentic images of the Narmer Palette—a ceremonial artifact traditionally associated with King Narmer (often identified with Menes), the First Dynasty ruler credited with unifying Upper and Lower Egypt:

Throughout this era, the influences between Upper Egypt and Nubia were considerable. The A-Group civilization was adept in utilizing the Nile’s resources, which mirrored the Egyptian developments in agriculture and trade that flourished in the surrounding regions. Nubian control of vital trade routes and resources such as gold and ebony positioned it as a crucial player in the regional dynamics. As trade flourished, cultural exchanges also took place. Artifacts from both regions show a blend of styles and motifs, indicating a rich tapestry of interconnection. Moreover, the emergence of a hieroglyphic writing system in Egypt around this time can be seen as an answer to the need for administration and control over increasingly complex social structures that were developing. Similarly, Nubian artisans contributed to this exchange by sharing their craftsmanship, evident in the pottery styles and burial practices that reflected both Nubian and Egyptian traditions.

The influence of the A-Group culture extends beyond its temporal existence. As it laid the foundations for subsequent cultural developments in the region, aspects of its societal organization, trade practices, and artistic traditions gradually amalgamated into what would become early dynastic Egypt. The religious practices of the time were increasingly characterized by the centralization of worship around specific deities, which foreshadowed the extensive pantheon that would later define the spiritual beliefs of Dynastic Egypt. The range of burial sites, such as those in Abydos, illustrates a transition towards more elaborate funerary rites, signaling the importance placed on the afterlife and the divine ruler—a concept that would dominate the future pharaonic ideology.

The cultural exchanges fostered by trade, as well as the interactions with contemporary cultures in surrounding areas, contributed to the gradual evolution that led to the unification of Egypt around 3100 BCE. Understanding the A-Group culture allows historians and archaeologists to trace the complex relations and transitions that shaped one of the most iconic civilizations in human history.

Timeline of Nubian Movement into Egypt