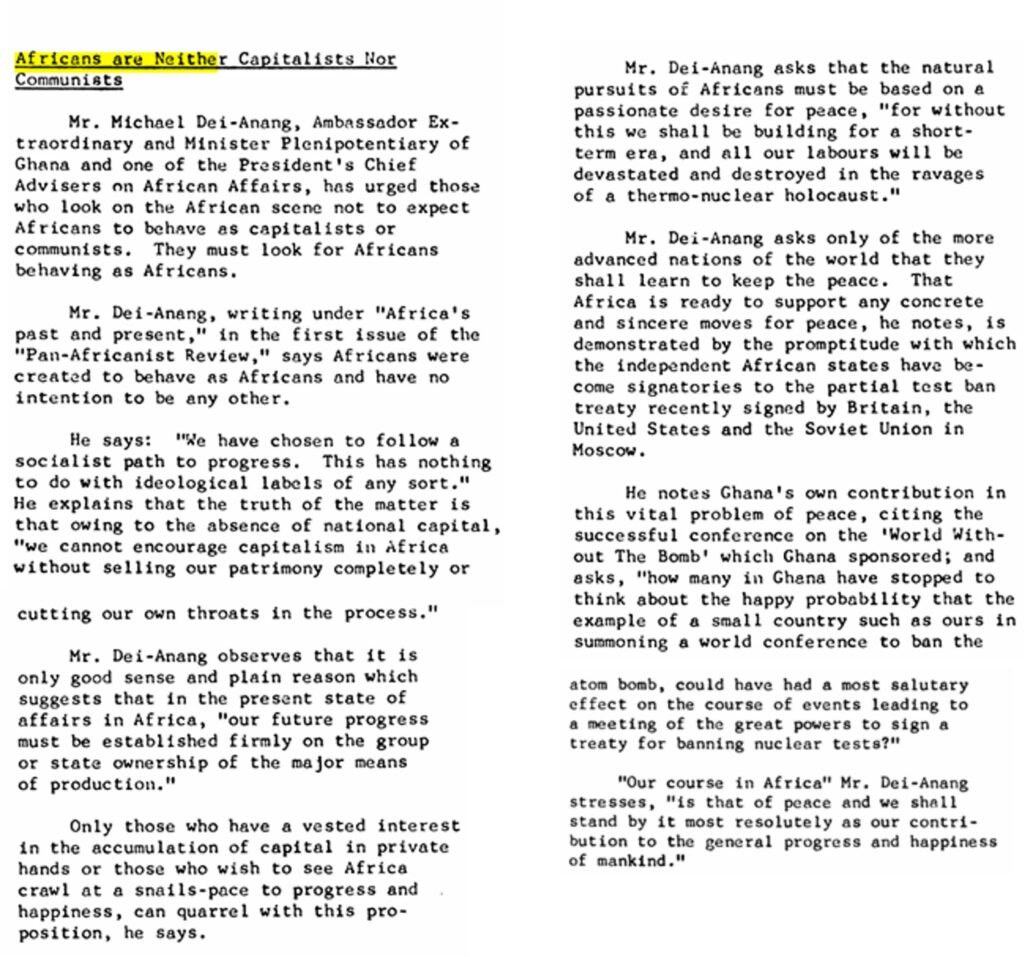

Africans are Neither Capitalists Nor Communists

The question of whether Africans are capitalists or communists is a complex one, deeply intertwined with history, culture, and socio-economic conditions. On the surface, many may assume that Africa, with its diverse nations and peoples, must align with one of these dominant ideological frameworks. However, a closer examination reveals that the reality is much more delicate. Africans often occupy a unique socio-economic space that doesn’t fit neatly into the categories of capitalism or communism.

To understand why many Africans might be categorized as neither capitalists nor communists, one must first consider the historical context. The colonial past has profoundly influenced African societies and economies. Prior to colonialism, many African communities operated under their own systems of governance, trade, and resource management. These systems often prioritized communal well-being over individual profit, reflecting a form of economic organization that differed significantly from both Western capitalism and Marxist communism.

Colonial powers imposed foreign economic structures that prioritized extraction and exploitation, leading to economic systems that serve the interests of external investors rather than local populations. The introduction of cash crops and the reorientation of local economies towards the demands of the colonial market further disconnected African economies from traditional communal practices. As a result, post-colonial African nations found themselves grappling with the legacies of these imposed systems, attempting to carve out economic identities in a world that had already defined them as peripheral.

In the post-colonial era, many African nations experimented with different economic systems, often adopting what could be described as hybrid models. Some governments embraced elements of socialism, aspiring to build states that provide for all citizens and manage resources collectively. For instance, through the leadership of figures like Kwame Nkrumah, the first President of Ghana, emergent from a colonial past.

Nkrumah and his contemporaries sought to redefine the continent’s identity and future through political ideologies that favored inclusivity, social justice, and collective resource management. Among these ideologies, socialism emerged as a crucial tool for nation-building, as Nkrumah and others aimed to create states that prioritized the welfare of their citizens. Julius Nyerere in Tanzania promoted ujamaa, a form of African socialism that emphasized community self-reliance and collective farming. Yet, these efforts often struggled against the realities of global capitalism, diplomatic pressures, and internal corruption.

Conversely, with the rise of globalization in the late twentieth century, many African nations shifted towards neoliberal economic policies—aligning more with capitalist ideologies. Countries like Nigeria and Kenya have embraced market-oriented reforms, encouraging foreign investment and privatization of state-owned enterprises. However, this transition has not been without challenges. Economic inequalities have often widened, and while a small class of entrepreneurs and business people has thrived under these policies, vast sections of the population continue to languish in poverty.

Moreover, the affinity for neoliberal capitalism and the influences of foreign multinational corporations have not led to a full embrace of capitalist ideology as understood in the Western context. Many Africans still uphold traditional values that prioritize community and family over individual wealth accumulation. The struggle to balance modern economic realities with deeply ingrained communal values often leads to a complex relationship with both capitalism and socialism.

Another significant factor to consider is the role of informal economies in Africa. A substantial portion of the African workforce operates outside of formal employment sectors, engaging in informal trade and community-based economies. This informal sector reflects a resilience and adaptability that does not align with strict definitions of capitalism or communism. It embodies a pragmatic approach to survival and community enhancement, prioritizing mutual aid, local resource management, and social networks over profit maximization or state control.

Many African nations also face ongoing issues related to governance, which complicates their economic identities.

Corruption, political instability, and weak institutions hinder the realization of both capitalist and socialist ideals. The failure of governments to build inclusive economies exacerbates inequalities, leaving many citizens disillusioned with both ideological extremes.

Additionally, social movements and local activism across the continent fuel a growing discourse around alternative development models that prioritize sustainability, equity, and social justice. These movements often critique both capitalist exploitation and state-controlled socialism’s shortcomings, advocating for new paradigms rooted in local realities. Concepts such as the African Renaissance emphasize reclaiming agency over economic and social systems, promoting self-determination, and fostering sustainable practices that respect both people and the environment.

In conclusion, Africans are neither strictly capitalists nor communists because their socio-economic realities and historical experiences do not allow for simple categorizations. Instead, they embody a rich tapestry of economic practices that reflect the complexities of colonial legacies, hybrid systems, informal economies, and unique cultural values. As Africa continues to navigate its future in a globalized world, it is essential to recognize and appreciate the diverse economic identities that emerge from its myriad contexts.

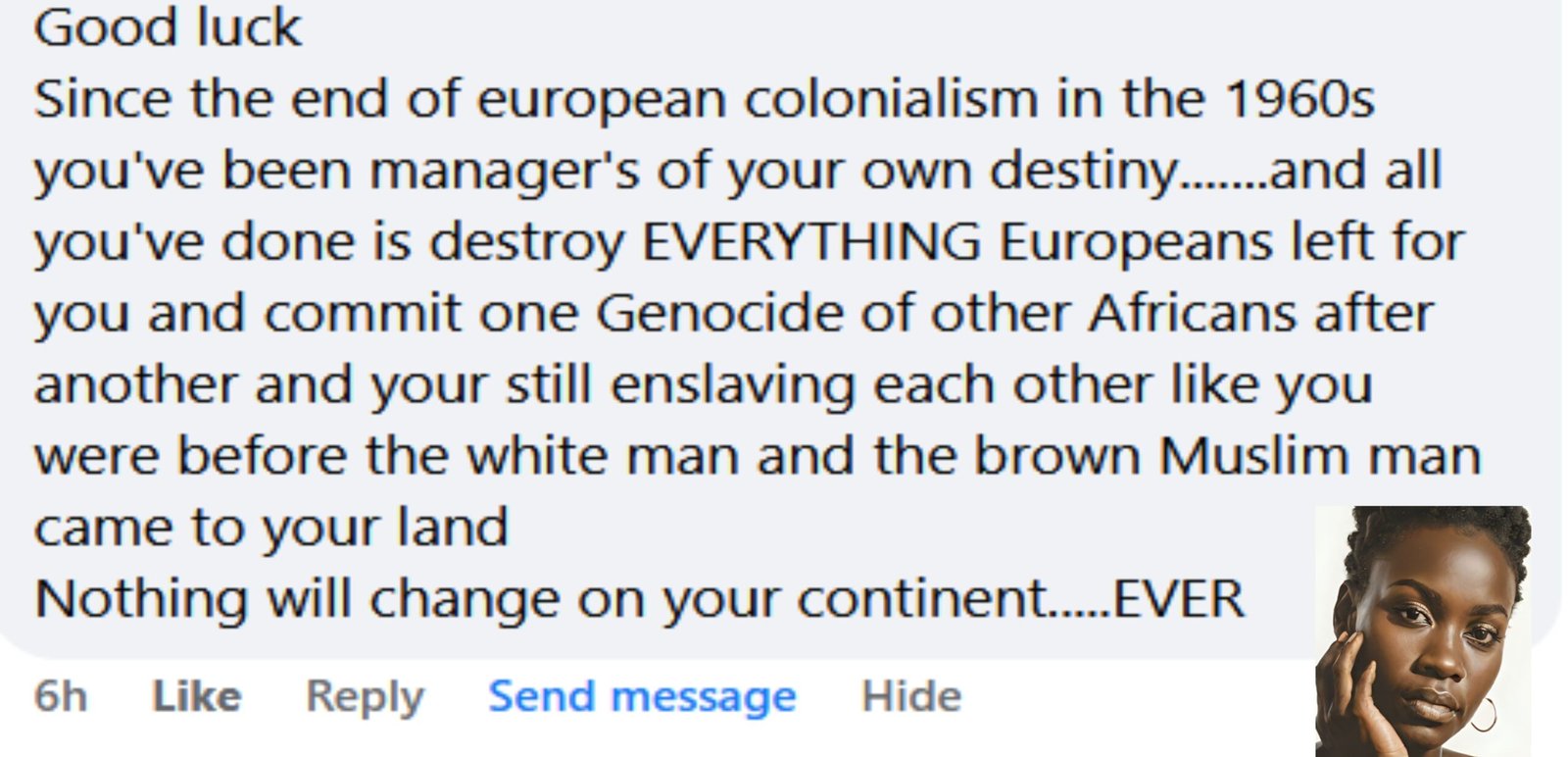

One thought on “Africans are Neither Capitalists Nor Communists”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Indeed, the so called capitalism in my opinion breeds greed and corruption. In the capitalists system, it is survival of the fittest. Al though self reliance is often encouraged under the capitalists system, the swift and the swindlers who know how to get around the system end up using the same resources that the masses are denied access to thereby creating a gap between the swift and the slow.

I think Africans have for thousands of years relied on each other for survival until their intermingling with European ideology.